Today’s note contains:

which Invite Press title is being considered for a design award

the reason you can't really sell a book with a bad cover

the history of the paperback

references to two books I'm currently reading

a shout out to Michael Buckingham

and so much more...

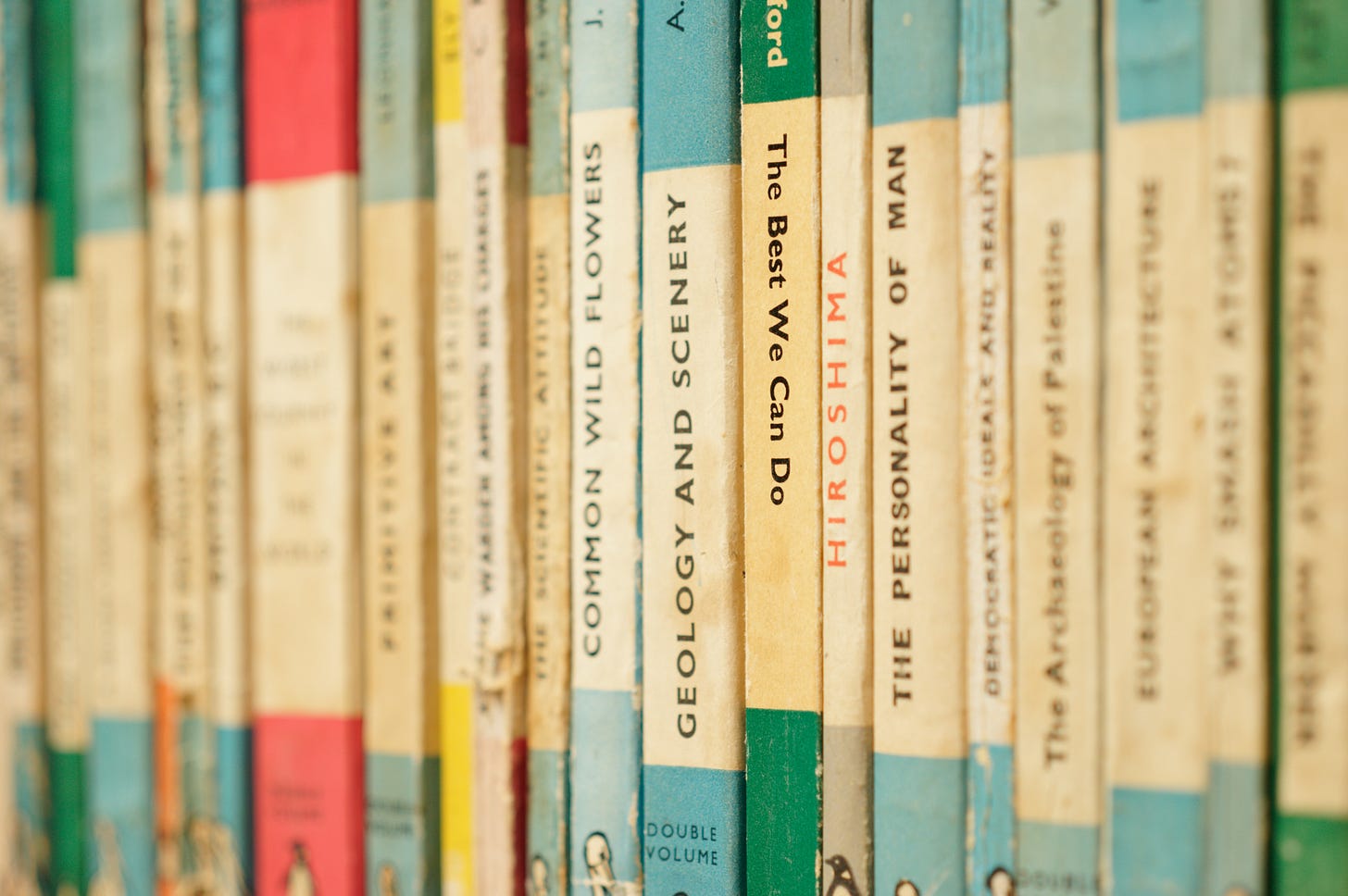

Photo by Karim Ghantous on Unsplash

1. Judging a Book

“People like to say that we don’t judge a book by its cover, but we all know that isn’t true.”

That’s a favorite line from Invite Creative Director Michael Buckingham. He understands that a good cover makes or breaks the success of a book.

A good cover is part of a beautiful book experience, which is part of our ethos at Invite. As I write this, one of my current reads is Ego is the Enemy, by Ryan Holiday. It’s a Penguin book and it’s beautiful. You just want to show people. Holiday is a stoic but his thesis on humility is fitting for Christians. (I envision a whole set on the fruits of the Spirit that models Holiday’s format.)

A less elegant term for “a beautiful book experience” is the package. The cover is important because it’s a big part of the overall package, and to minimize the power of the package is to hurt the potential influence of your idea. Talking about the failure of New Coke, Malcolm Gladwell writes,

Clever packaging doesn’t allow a company to put out a bad-tasting product. The taste of the product matters a great deal. Their point is simply that when we put something in our mouth and in the blink of an eye decide whether it tastes good or not, we are reacting not only to the evidence from our taste buds and salivary glands but also to the evidence of our eyes and memories and imaginations, and it is foolish of a company to service one dimension and ignore another.1

The Cover is About Trust

To understand why the package is so important, we need to take a quick look at one of the most important inventions in American history: the humble, ubiquitous cardboard box.

The cardboard box is a prime symbol of life today. It began with the genius of Albert Jones of New York City, who in 1871 modified stiff top hat liner paper to protect his bottles as he shipped them around town. Jones changed everything. As Benjamin Lorr writes in The Secret Life of Groceries, “regular shipments of products suddenly make economic sense.”2 Within ten years, 20% of all manufacturing in the United States is being shipped and presented in packaged containers.

With the emergence of boxes, a problem: manufacturers needed a way to distinguish their box from their competitor’s box. Whereas the general store once stocked rice and oats in barrels, devoid of unique marking and distributed by a local, trusted merchant, now consumers are given something new: choice. Consumers shift from a person—the merchant—to a box.

But that’s not the only shift. As the new transaction removes the person, it shifts the locus of customer trust. How does the customer know which box is best? Conversely, how does a manufacturer gain customer trust?

The result is a push toward better packaging. Lorr writes, “Modern life does not exist without this shift. Directly from the box springs the brand. From the brand, the advertiser.”

Ah - now we see the reason for cover design. It replaces us, as authors and publishers! Since we cannot physically meet our readers, our book covers become our trust brokers.

This week’s bottom line: The book cover is about reader trust. It’s a chance to prove your idea is worth their time.

(Lorr offers a definition for brand, as well: “A unique answer to a need that probably cannot be filled”. Much depth, wisdom, and strategic implication is housed in this sentence. But not yet. We will dive into marketing in a couple of months.)

Packaging eventually impacted every industry, publishing being a final one. (Church and publishing: partners in laggard living.) Since time immemorial, books have consisted of bound paper with plain, hard covers to protect fragile sheets. The quality of the paper and covers refined over time, as all innovations do. By the early 20th century, books had become quite high end.

They had also become quite expensive. To give you an idea, the best selling film in history opened in Atlanta, GA, on December 15, 1939. A ticket to Gone with the Wind that day cost 20 cents. By comparison, the hardbound book on which it was based cost $2.75. Adjusted for 2023 dollars, that’s a choice between a $4 movie ticket or a $61 book.

Not many people bought books in 1939.

Caring About the Cover is Respecting the Reader

That all changed when Robert de Graff released the first paperback. Like any revolutionary change, it seems simple in retrospect. But the entrepreneurial de Graff pulled off a minor miracle by altering business plans that seemed cased like stone to the hidebound publishing industry. The key, as with many advancements in business, was economy of scale, made possible by a radical expansion of distribution outlets.

de Graff made two big gambles. One, he thought there was an untapped market for books. As Andrew Shaffer writes, “New York publishers didn’t think cheap, flimsy books would translate to the American market.”3 That’s a nice way of masking highbrow hubris. Book buyers had to date trafficked boutique literary stores in major cities. de Graff’s model bet that he could sell books “in newsstands, subway stations, drugstores, and other outlets to reach the underserved suburban and rural populace.” de Graff respected the public—he believed that people who could read would want to read.

That was crazy talk. Traditional publishers did not believe the middle class wanted books. As it turns out, they did. Nobody had ever seriously investigated the possibility.

His second big gamble was to adapt the box revolution, with illustrated and branded packaging, to books. Hard bindings prior to de Graff had “stately, color-coded covers … which lacked graphics other than the publishers’ logos.” de Graff knew that less “literary” audiences could be aided by graphics and color. While keeping the text the same, he presented paperbacks with visual appeal.

After World War II, the paperback business shot to the stratosphere. Publishers and established authors didn’t like it, even though it helped them. George Orwell said, “if other publishers had any sense, they would combine against them and suppress them.” Orwell’s magnum opus 1984 appeared in 1948, the height of the paperback bull run. Yet his inclination was to resist the very change that propelled his success, proving that keepers of the status quo often stand by or actively resist successful change, even when that change proves beneficial.

Twenty years later, in 1960, paperback revenue finally surpassed hardcovers.

The highbrow hubris is humorous today. But be careful! Oddly, we have a tendency as authors to bring a form of highbrow hubris to our own work. In subtle ways, we demand that our readers come to us, through our word choice, our format and structure, and the cover and design of the book itself.

The hubris reflects a superiority that is antithetical to our message as Christians. Instead, let’s adopt the attitude of the servant, and work to earn the trust of our readers.

At Invite, we are driven by the message we carry to people. The reader experience begins with the book cover. While part of our job at Invite is to design great covers, the question for you is this:

Takeaway: From your word choice to your structure and overall message, how are you earning the trust of your reader?

2. Championing Invite

Yesterday I got an email from Jeff Crosby, President and CEO of the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association (ECPA). Invite is now an ECPA member, and we submitted a couple of books for their annual design awards. Jeff wrote,

Dear Len,

I am in the Arizona office with the rest of the ECPA team and we have been reviewing Top Shelf Design Award submissions prior to sending the copies to our judges. I simply wanted to commend you for both the incredible design and content of your book "Heirs of Eden" by David McDonald. Well done!

I look forward to meeting you in San Antonio.

Jeff

We also submitted That’s Good News by Shane Bishop, with its cool, populuxe comic book style. Originally, Shane liked it but was uncertain about the risky cover, until he showed some of his young 20-something staffers. They loved it. As Shane says, Bam!

Bishop’s cover was the first one designed created by our Creative Director, Michael Buckingham. Michael is pushing the envelope and bringing good packaging sensibility to each Invite title.

P.S. We are going to end up with ~15 of these posts about influence, which is about how to make a great book. After that, I am going to move into marketing. If you have a friend who may benefit from these weekly notes, send them here to our substack.

Malcolm Gladwell, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (New York: Back Bay, 2007), 165.

Benjamin Lorr, The Secret Life of Groceries: The Dark Miracle of the American Supermarket (New York: Avery, 2020), 26.

Andrew Shaffer, “How Paperbacks Transformed the Way Americans Read”, April 19, 2014, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/12247/how-paperbacks-transformed-way-americans-read.