Both reading and reading comprehension, or literacy, are declining—alarmingly so. As a Christian publisher, my mission is tied to reading. Yet now we live in a TLDR culture: “too long, didn’t read.”

What does this mean for publishing and for the mission of the church?

First, let’s consider several reasons why reading has declined, according to a recent essay from the Chronicle of Higher Education:

The 2020-21 pandemic, which created a decline in academic expectations.

Bad reading-instruction strategy from twenty years of dumb decisions in education methodology.

Testing culture and an instrumental approach to education, which has implicitly taught that reading is not a foundation for learning but an instrument for referencing data.

The rise of mobile technology, including smartphones and social media, which has offered powerful new alternatives for our time.

The dis-incentivization of “equitable grading”, which has lowered standards.

Generational decline in reading habits—a continuation of long-term trend.

A decline in the quality of educators and pedagogy due in part to the challenges in education from the above factors, as well as low pay and high time demands.

Mental health and the fear of being isolated.

Here is a study the article cites on the decline in reading, and another study on the decline in comprehension. As one learns how to read by reading, and how to write by reading, it stands to reason that the decline in reading is leading to a decline in literacy itself.

The decline in reading is leading to a decline in literacy itself.

Great Books professor Adam Kotsko calls it a “conspiracy without conspirators.”

English professor Theresa MacPhail is more blunt: “There’s something broken in American culture.”

From Print Culture to Digital Culture

It’s pretty indisputable that not only is reading down, but literacy has suffered.

But does that mean our culture is “broken”?

In my first book, The Wired Church, written in 1998, I argued that the rise of new, image-centered modes of communication were already creating different modes of literacy, and that by adopting the mode of a print culture Chicken Little, bemoaning the decline and fall of civilization, we were fundamentally misunderstanding the need and opportunity to adapt our communication to a rising “electronic”, now digital, culture.1

Around the same time, journalist Mitchell Stephens prophetically argued that Western culture was undergoing a gradual, tectonic shift from print culture to digital culture. Every major shift in communications technologies brings social upheaval, a decline in the old forms of learning, the gradual re-formation of systems and even values based on the features of the new technology, and the eventual rise of new forms of literacy. He writes, “image is replacing the word as the predominant means of mental transport.”2

“The means we use to express our thoughts… change our thoughts.” - Mitchell Stephens

For example, the printing press moved culture away from oral learning and encouraged silent, individual and detached reading and reflection of long-form argumentation. The result was a culture of detached, rational thought, which eventually led to the Enlightenment. (But not before Western civilization suffered through a few wars. Several scholars have drawn lines between the rise of the printing press and eventual armed conflict.)

The driver is the change in our communications technology, which brings with it different modes of learning and ultimately different values.

Now the rise of visual technologies from color television to the present has driven a multi-generational shift, not only in how we learn but in how we think. The age of mobile phones and social media has favored speed, personal experience, a loss of social context and a rise in groupthink.

The bottom line: We shape technology, and then our technology shapes us.

The Upside of Digital Culture

Clearly, the rise of digital technology has a significant role to play in our current cultural moment.

While what we are seeing happen in culture today may seem mysterious and concerning to some, it is possible to understand not only what is happening, but why, and where it’s going. The maturation of a shift in communication systems are historically slow to form and sudden to flower. The “brokenness” MacPhail names is actually indicative of a shift from print to digital culture, or as Stephens names in his book’s title, the rise of the image, the fall of the word.

This change is both good and bad. If technology does anything for us, it merely magnifies human tendencies both to do good and cause harm.3

The paradox of progress is that every technology brings both downsides and upsides.

New communication systems disrupt and destroy old forms of learning. But here’s the good news: they also come with significant new advantages, if we can learn to harness them.

So instead of crying about what we have lost, what is we ask, what are we gaining? What are some upside features that we should consider how to harness?

Certainly, our still forming digital culture emphasizes mobility, visual learning, and social context, to name a few features. But let me offer two fundamental opportunities of literacy in the digital age:

One: Greater Speed.

Changes in communications systems always start slow then seem to come on suddenly.

Some argue that technological assimilation occurs at ever increasing rates. And it’s certainly true that two-way, global video communication is a 21st century phenomenon.

But a message that’s motivated has always had fast feet, regardless of what technology it’s wearing. Using the still relatively new printing press, Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses in 1517, and was quickly confused at how he went viral. He wrote to the Pope less than a year later, “it is a mystery to me how my theses were spread to so many places.”4

“It is a mystery to me how my theses were spread to so many places. - Martin Luther

Imagine the power of a message as urgent as Luther’s—one people are eager to receive—combined with the power of 21st century communications technology.

Two: Greater Spread.

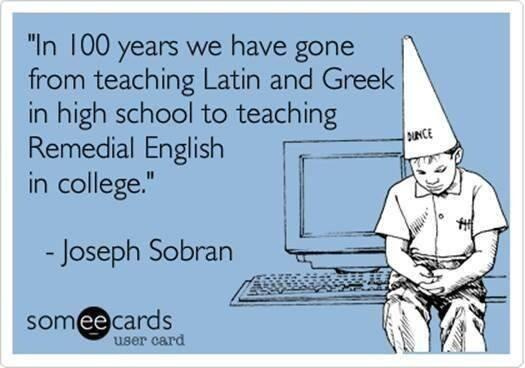

The Latin meme above fails to mention that only a privileged few received educational instruction a century ago, while the vast majority receive educational instruction today. Political scientist Martin Gurri argues that the “revolt of the public” we see today is not a decline in democracy, but actually a fuller expression of democracy.

Now, everyone has access.

What better news for a church with a message for all people?

Harnessing the Power of Digital Culture

What does all of this mean for your current todo list?

The opportunity for us as gospel communicators is to learn how to leverage what our new technology has wrought.

As Publisher of Invite Press, I’ve witnessed shifts in digital culture just since we began in 2020. The first two decades of the 21st century emphasized a style of non-fiction writing defined by integrated, story-driven argumentation, a la Malcolm Gladwell. This may be over. Now, I am seeing a change in writing styles that work:

Shorter books.

Shorter chapters.

More bottom line driven.

Punchier presentation of ideas.

Less heavily cited argumentation.

Oriented around solving immediate problems.

Short anecdotes rather than longer narratives.

Critically, we are also seeing content diffused across multiple platforms, which gets back to a post I wrote last year: not books, but product lines.

As we move forward, we’re looking at multi-modal delivery of content, which simply means that as an author, you are thinking about how to put your content into as many modes of delivery as possible.

Takeaway: If you want to sell books in 2025 and beyond, emphasize features that work in digital culture. Solve problems. Consider how to present your content across multiple media. Take your ideas to where people already consume content. Give them authentic solutions formed out of your life expertise.

Wilson, Len. The Wired Church: Making Media Ministry. Nashville: Abingdon, 1999, 33-34.

Stephens, Mitchell. The Rise of the Image, the Fall of the Word. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, 21.

Wilson, Len. Greater Things: The Work of the New Creation. Plano, TX: Invite Press, 2021, 54.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth. The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005, 160.